Tags

1974, austerity, baldwin, bbc, Coalition, conservative party, david cameron, edward heath, elections, general election, harold wilson, hung parliament, jeremy thorpe, labour party, liberal party, minority government, north sea oil, scotland, scottish national party, snp, sunningdale, swingometer, ulster unionism

With just a few days to go until Britain votes in a new House of Commons, speculation is rife about what will happen if the polls turn out to be correct and there is a hung parliament. Who will get the first chance to form a government? Who will be prepared to do a deal with whom? And, how long will we be without an elected administration?

As people try to get their heads around all this, history offers us the very recent example of 2010. But the consensus seems to be that things will almost certainly run differently this time. Parties may be in less of a rush to do a deal; indeed, there may be no formal deals at all. Neither of the main party leaders may be able to claim convincingly that they have been more victorious than the other, and so minor parties may feel empowered to seize the initiative in shaping the future. Other possible scenarios, different from the Cameron-Clegg rose-garden deal, therefore need to be considered.

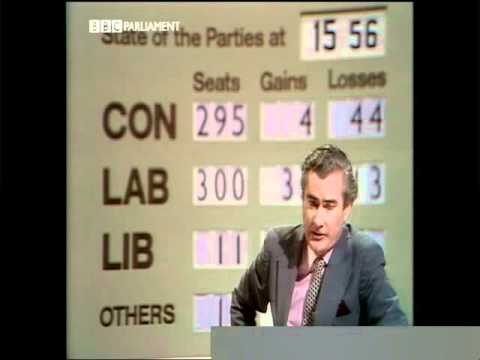

History helpfully offers the example of 1974 as well, one of just two years in the twentieth century when two general elections occurred. In the first election, in February 1974, Edward Heath’s governing Conservative Party lost its majority and Harold Wilson’s Labour Party increased its number of MPs by 20. With all the votes counted, however, Labour was still short of an overall majority by 17 seats, with 301 MPs to the Conservatives’ 297. In the ensuing hung parliament, Labour went on to govern as a minority, but just eight months later, in October 1974, Harold Wilson decided to go to the polls again, and this time won a wafer-thin majority of 3.

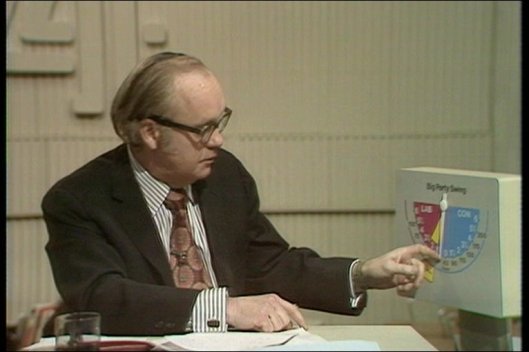

Was it harder to predict a close result in 1974? Less technology and fewer opinion polls certainly meant more tension on the night.

Even at a glance, the events of spring 1974 help to make a few things clearer about what might happen next week. First, although he had obviously lost his majority, Edward Heath, as the incumbent prime minister, still got the first chance to form a new administration – this was seen as what the unwritten constitution guaranteed. Secondly, both politicians and the media thought it highly significant that, while Labour had won more seats, the Conservatives had (narrowly) won the popular vote: by 11.9 million votes to 11.6 million, a margin of 0.7%. In the days following the result, this seemed to cast a cloud over the issue of who had the “right to rule”. Finally, small parties – at that time the Liberals, the SNP and the Ulster Unionists – which might have been expected to do everything they could to maximise their chances of attaining power, actually stuck to entrenched positions making life difficult for their larger rivals.

Many people saw it as completely illegitimate that, after losing 37 seats, Heath tried to hold onto power.

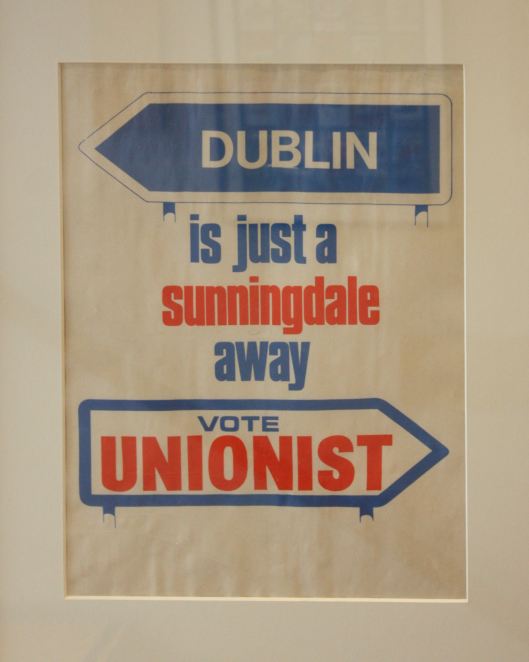

Certainly, there was no relying on the Conservatives’ old allies, the Ulster Unionists, who had been incensed by the Sunningdale Agreement.

The official record of Heath’s attempts to cobble together a workable majority in the days after the election are contained in a series of confidential annexes to the Cabinet Papers. I have reproduced these annexes in full below. (Wilson’s simultaneous horse-trading is not a matter of public record because, at the time, he was still not Prime Minister.)

Among the things the annexes reveal are Conservative ministers’ conviction that there was a “large anti-Socialist majority” in the country (nearly 12 million Conservative votes and 6 million Liberal ones) and that this could be a legitimate way of determining who had the right to govern. A similar calculation was used in 1924 to try to convince Stanley Baldwin not to allow Ramsay MacDonald into power. Other continuities include the Liberals’ enduring price of cooperation: electoral reform. This was also among their demands in 2010. Will it feature again in 2015?

But bread-and-butter issues about wages and the cost of living were still at the core of electoral politics. SOURCE: Daniel Meadows, http://we-english.co.uk/blog/2009/05/15/daniel-meadows-photobus/

However, what simultaneously represents the biggest continuity with the past and the biggest difference is Europe. In deciding which parties to work with, the Conservatives’ 1974 attitude to Europe was key. On this basis, they ruled out any cooperation with the Scottish Nationalists and came to believe that a Lib-Con pact was possible. Last night’s BBC Leaders’ Debate revealed that Europe will be a key issue this time. But the big difference, of course, is that, in 1974, the Tories all wanted to stay in the European Community, while it was the SNP and Labour that wanted to leave it!

Over the course of a single weekend, between 1 and 4 March, Edward Heath decided to capitulate. The minutes formally record his thanks to ‘his colleagues for their loyal support during their years in office’. What they also show is how his decision was informed by both matters of principle and low politics, for instance, the possible impact of allowing Labour to take credit for North Sea oil revenues. We can probably expect similar scheming and shrewdness in the days (and weeks?) ahead.

CONFIDENTIAL ANNEX – Friday 1 March 1974 at 5.45pm

THE SITUATION FOLLOWING THE GENERAL ELECTION

THE PRIME MINISTER said that the result of the General Election was disappointing for the Government and also confusing to interpret. Although a number of results were still outstanding it was clear that no one Party would be able to command an overall majority. The Labour Party could not get more than 301 seats and the Conservatives might obtain as many as 299: and it was difficult to forecast where the Liberals and other small Parties would stand in such a situation. The Government seemed to have three courses open to it. The first would be fir him to advise The Queen that she should send for Mr Wilson as the probable leader of the largest single Party even though he would be able to form only a minority Government; and the Labour Party had indeed issued a statement indicating its readiness to attempt this task. The second course was for the Government to exercise its constitutional right to face Parliament and see whether it could command support for its programme. The third course was to try and arrange support from the smaller Parties for a programme designed to deal with the nation’s immediate difficulties. So far as this last course was concerned, support from the Ulster Unionists must be regarded as unreliable, although they might decide to support the Government without trying to insist on any deal, which would be unacceptable, over the Northern Ireland Assembly or Executive. An alternative basis of support would be to consult the Liberal Party as to their willingness either to enter a coalition or to support the Government in the lobbies on an agreed programme. He would welcome the views of his colleagues on these three alternatives. In particular it was necessary to consider carefully whether in a situation where the two main Parties were so close, where the Conservative Party had obtained the majority of the total votes cast and where nearly 6 million votes had also been cast for the Liberal Party, the nation would expect him to attempt the formation of a right-centre coalition before handing over power to the Labour Party. He had spoken by telephone to the Secretary of State for Employment who was ill: and the latter favoured an approach to the Liberals. This would however involve taking the latter into full confidence about the economic situation. A further complication was that the Government did not yet know what the Pay Board would recommend for the miners or whether the latter would accept it and agree to return to work under a Conservative-Liberal coalition: the likelihood was however that the recommendations would be generous and would be accepted irrespective of the Government in power.

In discussion it was argued that, although the Government had not obtained the strong mandate which it had sought, there was a large anti-Socialist majority which supported both an incomes policy and Britain’s continued membership of the European Community. This majority could form the basis of a Conservative-Liberal coalition which would unite the moderates in the country. It was also arguable that the public opinion polls had encouraged many traditional Conservative voters to feel that they could safely vote Liberal because of doubts about some aspects of the Government’s policy but still see the return of a Conservative Government. The response of the Liberals was difficult to predict. They might well demand too high a price in terms of electoral reform: on the other hand they would be unlikely to want to face another General Election at an early date and might therefore be inclined to reach an accommodation. From the Conservative Party’s own point of view there were also arguments both for seeking an accommodation and for accepting without delay the consequences of not having obtained an overall majority. If they went needlessly out of office, a Labour Government would attribute the economic situation to Conservative mistakes and, with the later benefit of North Sea oil, might remain in power for a very long period. On the other hand if a coalition was formed with the Liberals, those traditional Conservative supporters who had voted Liberal on this occasion might never return to their former allegiance.

In further discussion there was much support for the view that the Liberals held the key to the situation and that they should be forced to show whether they wished to keep in power a Conservative or a Labour Government. It would clearly be wrong for the Conservative Party to hang on to power at the expense of its principles: but the chances of reaching an acceptable accommodation with the Liberals could only be assessed as a result of consultation with them. This would force them to move one way or the other: and if they refused an accommodation the traditional Conservative voters who had voted for them would be likely to return to their former allegiance at the next Election.

THE PRIME MINISTER, summing up the discussion, said that the general view of the Cabinet was that he should consult the Leader of the Liberal Party about the chances of a coalition or an arrangement whereby the Liberals would support an agreed programme to deal with the immediate situation. The object would not be to do the best possible deal with the Liberals but to force them to show their hand and to discover the sort of programme which they would support. In the present situation where no Party would command an overall majority the Government had either to be rejected by the House of Commons or by the Liberal Party and there was every reason to canvass the possibility of an anti-Socialist coalition. His approach to Mr Thorpe would however be without commitment, and members of the Cabinet should remain in London over the weekend so that he could consult them further as the situation developed. In the meantime no indication should be given to the Press of the Government’s intentions. He would be having an Audience of The Queen immediately after their meeting and a Press statement would say simply that he was going to report to her on the situation.

The Cabinet –

Took note, with approval, of the Prime Minister’s summing up of their discussion.

CONFIDENTIAL ANNEX – Monday 4 March 1974 at 10.00am

THE SITUATION FOLLOWING THE GENERAL ELECTION

THE PRIME MINISTER said that he had kept in close touch with most of his colleagues over a weekend of intense consultation but it was right for the Cabinet as a whole now to take stock of the position reached. It had been argued by some that the support of

the Ulster Unionists would provide a sufficient majority to continue in office but this would be both difficult and unreliable. As envisaged at their last discussion he had therefore seen the Leader of the Liberal Party at 4.00 pm on Saturday 2 March. Mr Thorpe had agreed that the Liberal attitude on incomes policy and on Europe was similar to that of the Government and that it was constitutionally proper for the latter to explore the possibility of Liberal co-operation on a general programme of measures to be included in The Queen’s Speech or indeed Liberal participation in the Government itself. Mr Thorpe had not been authorised by his colleagues to accept any arrangement but he had asked a number of questions. The first concerned Northern Ireland, and he had been assured that the Government would not contemplate any deal with the Ulster Unionists but would continue to support the Sunningdale agreement. He had then asked about electoral reform, making it clear that he was not wedded to any particular solution although he had mentioned the possibility of proportional representation for the boroughs and the alternative vote system for the rural areas: on this the Prime Minister had said that he could give him no indication of the Government’s view without further consultation with his colleagues. He had also mentioned the Kilbrandon Report on which he had been told that the Government had undertaken some preliminary work which could be discussed with him later. He had not raised any foreign policy or economic issues, but had said that his Parliamentary Party would not be meeting until 4 March although he could consult some of his senior colleagues on the following day. After doing this he had telephoned the Prime Minister at 5.30 pm on Sunday saying that things were moving in a helpful direction. There were however two problems. The first concerned the leadership of the Conservative Party if Liberal support was to be provided: but on this he felt he could handle his Party. The second was electoral reform on which the Liberals would expect specific and urgent action. If this was promised the Liberals would consider support for the Government and did not rule out the possibility of entering a coalition at a later stage.

The Prime Minister had been in touch with many of his colleagues both following his initial talk with Mr Thorpe and the later telephone conversation. They had increasingly come to the view that an arrangement for Liberal support would be insufficient given the measures which would have to be taken to restore the economy. A coalition seemed the only possibility, but on electoral reform they had not felt able either to commit themselves on what they would recommend or still less to what a Speaker’s Conference might decide. They were not therefore in a position to deliver on the matter which was most important to Liberal thinking. The most that might be contemplated was to acknowledge the strength of Liberal views, to offer the setting up of a Speaker’s Conference as a matter of urgency and to say that they would thereafter ask Parliament on a free vote to decide upon the Conference’s recommendations. He had therefore seen Mr Thorpe a second time at 10.30pm on Sunday evening. He had explained the position to him and had said that he would try to let him have the Cabinet’s view before the Liberals’ own Parliamentary Party meeting at 11.00am that morning. He had said that he personally felt that coalition was essential and that the most that could be offered on electoral reform was a Speaker’s Conference. Indeed he had stressed that he could not honourably undertake to deliver more than this. Mr Thorpe had repeated that he could not enter a coalition at this stage although many in his Party wanted an arrangement with the Conservatives. The offer of a Speaker’s Conference would however be insufficient to secure this and as a minimum the Liberals would expect a statement by the Government that they regarded some change in the electoral arrangements as necessary. Mr Thorpe had also said that Mr Wilson also wished to see him but that he would take the same line with him over electoral reform.

THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR ENERGY said that he had seen Lord Byers who felt strongly that a coalition would be the end of the Liberal Party. He favoured an arrangement with the Government with proportional representation as the price, but felt that the Liberal Party might not be prepared to go as far even as this.

THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EMPLOYMENT said that the Pay Board report on miners’ relativities had now been received although he had not yet read it personally. It offered big increases in miners’ pay which the Liberals would certainly support: but it was now questionable whether the miners would accept it from a minority Government with Liberal support only. This was a further factor to be taken into account in considering the alternatives of Liberal support or coalition. Indeed the latter might in any case be necessary to bind the Liberals to a settlement not in excess of that proposed by the Pay Board.

In discussion there was general agreement that the matter now needed to be brought to a head urgently both from the national and Party points of view. There had been widespread support within the Conservative Party for the approach to the Liberals but the Government’s backbench supporters were increasingly worried by talk of a deal with the Liberals over proportional representation and were unlikely to support any action leading towards that end. An arrangement with the Liberals would in any case be insufficiently stable, and Mr Thorpe seemed to be asking too much and offering too little. There was no possibility of an arrangement with the Ulster Unionists who would seek to undermine the Sunningdale agreement, or with the Scottish nationalists who were left-wing and opposed to the Government’s European policies: and a decision to face Parliament without guaranteed support to provide an overall majority would seem to many to be a discreditable attempt to hold on to power and would exacerbate relations with the trades unions. At some stage the political and economic situation of the country might dictate a Grand Coalition between the Labour and Conservative Parties but talk of this was premature. It had been right to make an approach to the Leader of the Liberal Party but it was now clear that an offer of general support by that Party would not provide the stability necessary for the Government to remain in office. Unless therefore the Liberal Party was prepared to enter a coalition without a commitment to legislation on electoral reform in the new Parliament – and this seemed very unlikely in the light of Lord Byers’ remarks – there seemed no alternative to the Prime Minister tendering his resignation to The Queen and advising her to ask the Leader of the Labour Party to form an Administration.

THE PRIME MINISTER, summing up the discussion, said that the Cabinet were agreed that only a firm coalition with the Liberal Party could ensure their continuance in office, and also that it would be inadvisable to offer more to the Liberals than a Speaker’s Conference on electoral reform in order to obtain such a coalition. The chance of this proving acceptable now seemed remote but it would be necessary to await a formal reply from the Leader of the Liberal Party before tendering his resignation. It was therefore necessary to send Mr Thorpe a letter forthwith confirming the offer of a coalition with a Speaker’s Conference on electoral reform, but making it clear that the Conservative Party could accept no commitment to legislation on electoral reform in the new Parliament since the electorate should have an opportunity to express their views on the changes proposed. He had prepared a draft for this purpose, the final text of which he would settle in consultation with a few of his senior colleagues. On the assumption that Mr Thorpe rejected this proposal outright this might be the last meeting of the present Cabinet and he wished to thank his colleagues for their loyal support during their years in office.

THE LORD CHANCELLOR said that the members of the Cabinet would for their part want to thank the Prime Minister for the leadership which he had given to them.

The Cabinet –

Took note, with approval, of the Prime Minister’s summing up of their discussion, and warmly endorsed the remarks of the Lord Chancellor.

CONFIDENTIAL ANNEX – Monday 4 March 1974 at 4.45pm

THE SITUATION FOLLOWING THE GENERAL ELECTION

THE PRIME MINISTER said that a reply had now been received from the Leader of the Liberal Party to the letter which had been despatched to Mr Thorpe following the meeting of the Cabinet earlier that day. In it Mr Thorpe, as expected, had rejected the proposal for a Liberal presence in the Government: but had instead suggested the calling of a conference between all the Party Leaders with a view to the formation of a National Government. Although in his view this suggestion was not a practicable one, he had judged it advisable to reconvene the Cabinet. At their earlier meeting the view had been expressed that at some stage the political and economic situation of the country might require the formation of a National Government, but there had been agreement that the time for it was not ripe. He did not see that Mr Thorpe’s proposal called this judgment in question. There was too great a difference between the policies of the Conservative and Labour Parties, and the Leader of the Labour Party would almost certainly rebuff an approach at a time when the economy might be thought to be about to recover from the three-day week rather than enter a new period of crisis. He saw no reason therefore to alter his decision to tender his resignation to The Queen although in his reply to Mr Thorpe he would make the point that if a Labour Administration were formed and pursued Mr Thorpe’s idea he would consider very carefully an invitation to a meeting of Party Leaders.

The Cabinet –

Took note, with approval, of the statement by the Prime Minister.

Thanks. Fascinating. Regards Thom.

Thanks, Thom! Appreciate it.

If you fancy a break from political brow knotting come on over to the Jukebox! Thom.